Boosting Wind Project ROI

Technology

Authors

Johannes Maidl

Commercial Senior Specialist, Sales Analytics

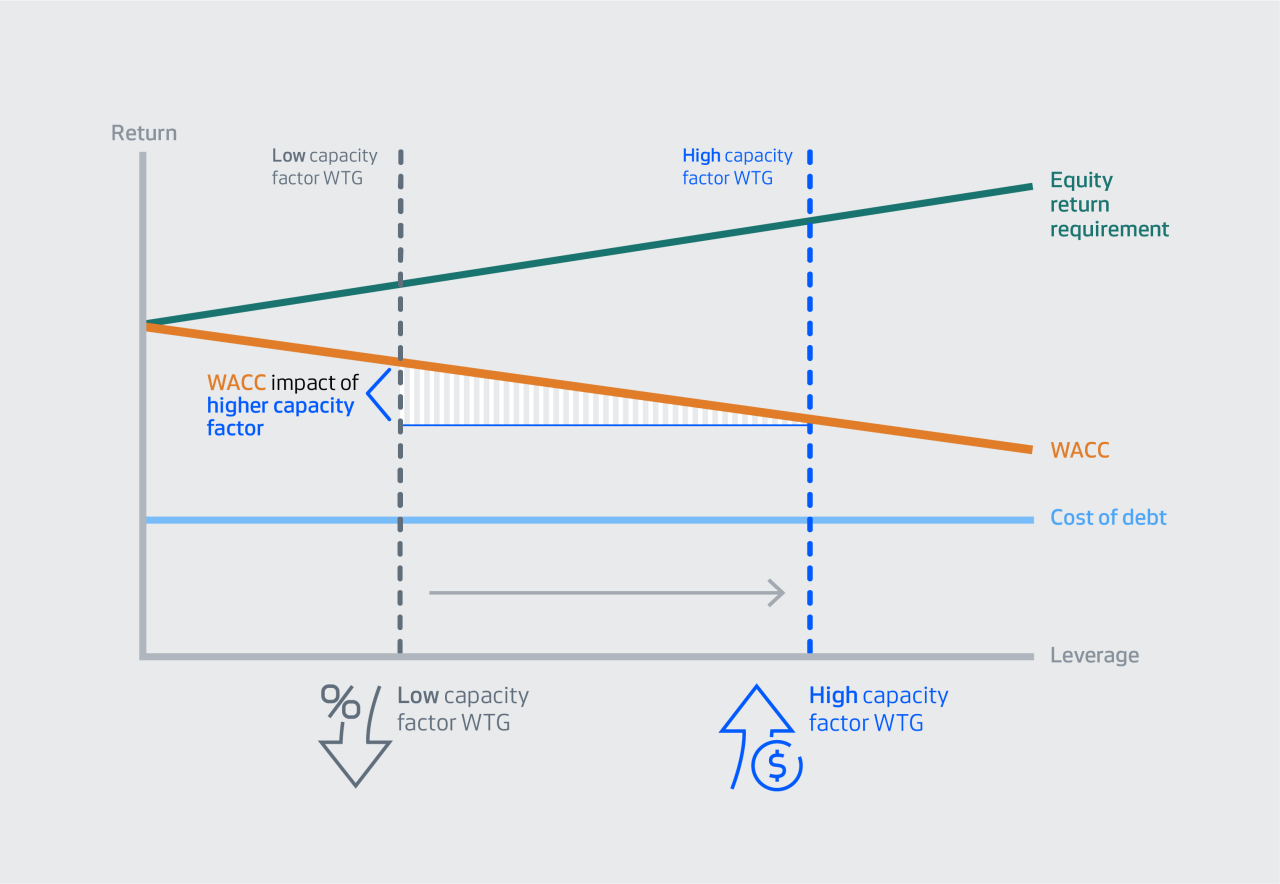

Getting lower WACC with high capacity factor turbines

In times of financial challenge, the choice of wind turbine type can contribute to critical extra profitability in wind projects.

Two developments hampered the global economy in 2022: galloping inflation due to cost increases in goods, services and raw materials, and interest rate increases of a speed and magnitude not seen in decades, which made financing these higher costs even more challenging. This combination was particularly hard on investments vulnerable to high financing costs, such as those with long lifetimes. Wind farm investments fall into that category.

Unless an investor takes a wind farm on their balance sheet, wind farms typically rely on project finance. This means they need to generate cash flows large enough to repay a loan while still yielding a profit large enough to meet the investor’s profitability requirements.

Project finance is based on two sources of capital: equity and debt. Equity is money sponsored by investors while debt is borrowed money. The cost for both is ultimately a combination of a so-called ‘risk-free rate’ and a premium. The risk-free rate is often proxied by the interest on government bonds, such as US Treasury bonds. The premium in the cost of debt is the lender’s fee for providing a loan, while the premium in the cost of equity is the extra percentage an investor expects compared to a safer investment at the risk-free rate. This equity premium differs between investors as it depends on the alternative investment opportunities they might have. In any case, equity premium is generally higher than the fee charged by a lender for providing debt, which has a negative impact on a company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) - the average rate it expects to pay to finance its business.

Since the cost of equity is typically higher than the cost of debt, one of the main objectives in project finance is to maximise the share of debt in the capital structure while minimising the share of equity.

The amount of debt provided to a project is determined by the lender through a calculation that assesses how much debt a project can carry - even in a scenario when things turn out worse than expected. If a project goes better than expected, a lender doesn’t get a piece of the upside; but if things go wrong, then the project might default on the loan.

The established process for this assessment is to calculate the project’s expected cash flow in each period and then to check whether this cash flow covers the debt repayment and interest payment by a safety margin, which the lender feels comfortable with – so called ‘debt service coverage ratio’.

One lever to increase the share of debt in the capital structure is the choice of turbine: at equal LCOE, a turbine with a higher capacity factor generates a higher cash flow. This then allows the project to shoulder a higher share of debt, allowing the investor to reduce the share of equity. As a result, this reduces the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). Reducing this rate is especially relevant in periods with high interest rates, like today.

Unfortunately, the impact of turbine choice on the WACC can go unrealized, as in practice the choice of turbine may be made before a lender is contacted for a loan offer. Nevertheless, pulling this lever can contribute to critical extra profitability in today’s wind projects.